Jennings Backus

Above is an AI-generated image of J. Dave Backus based on an actual photo from 1999.

“Continuity”

Jennings David “Dave” Backus, Jr., was born in December, 1943, the son of Jennings and Dorothy Pearl Backus, who were originally from West Virginia. When Dave was a toddler, the Backus family settled in southwestern Coffee County, Tennessee, near the distillery that, as an adult, Dave would serve for decades.

Backus’s personal as well as his professional story is almost entirely intertwined with that of Cascade Hollow. By his own account in a 2001 interview, he said he had “worked for Dickel all [his] life,” rising steadily through the plant to become Master Distiller in 1978. Dave came up through Cascade Hollow the old-fashioned way: by making whisky, day after day, until the craft felt like utter second nature (Note that since its post-Prohibition reintroduction, the plucky Dickel brand has insisted on spelling “whisky” the Scottish way, without an ‘e,’ “Because [its] whisky was just as good as anything from Scotland.”).

At one point, during a difficult time for the brand, Backus was distilling and simultaneously carrying the title of company president, a feat nearly unheard of by today’s standards. The Dickel whisky that Backus had inherited from Tennessee Whiskey legend Ralph Dupps was a distinctive product, defined first by the then-understated but now famous maple-charcoal mellowing step before barreling. When asked to explain what set Dickel apart from its neighbor Jack Daniel’s, Backus emphasized the distillery’s temperature-controlled approach to that process, “Kept below 50 degrees,” the man-of-few-words replied. The process known as cold filtering which had originated in icy Tennessee spring-fed creeks in the 1800s, is still considered an important part of Dickel’s house character to this day.

In 1997, the George Dickel brand was purchased (and is still owned) by spirits behemoth Diageo. The acquisition occurred right after that company’s formation from the merger of Dickel’s then-parent Schenley Industries-owned Guinness, and London’s Grand Metropolitan. Through the takeover, neither Backus nor Dickel’s consistency wavered, but by 1999, Backus faced what would become his tenure’s defining crucible: after years of heavy production, Dickel shut down distilling from 1999 to 2003 to work through surplus inventory. Outsiders worried; insiders called it an inventory correction. Backus told interviewers the pause was a practical step: “Hard to anticipate demand ten years into the future,” Dave calmly explained. His steady hand showed in the details he continued to mind: weighing grain by hand, relying on the cold spring that had always fed Cascade Hollow, and keeping the traditions intact until the stills could run again. Sure enough, by the autumn of 2003, the “sippin’ whisky” was again free-flowing. Contemporary newspaper accounts placed Backus in the stillhouse for the restart. Dave was making whisky the same as his predecessors and reassuring drinkers that patience and judicious stock management would bear fruit, (although it was almost too late to prevent a slight shortage of flagship Old No. 8 in the market by 2007).

In the lull, Dickel’s pause became a silver lining: some batches of No. 12 laid down in the previous decade had matured far beyond their target age. Backus acknowledged that older stocks had made it into bottle—twelve years old in some cases, roughly twice the intended age. Enthusiasts still point to those early-2000s bottlings as a happy accident of the shutdown; in some parts of the country, bottles of 12-year old “accident” were fetching 8 times what a normal bottle of George Dickel No. 8 called for.

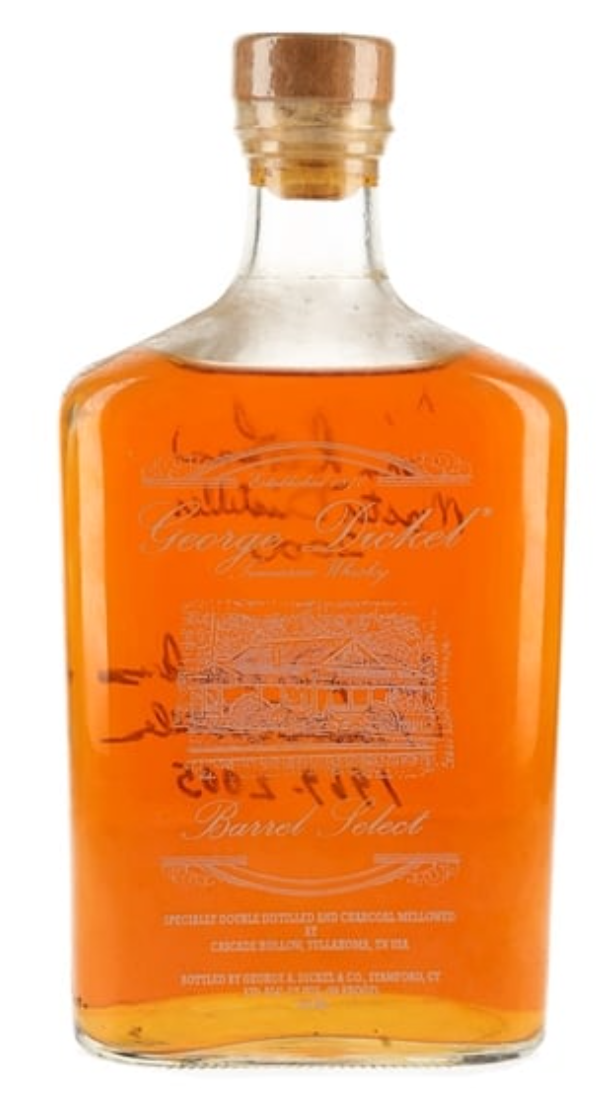

As the hibernating distillery roared back to life, Backus also took care of succession. In 2004 he recruited a brilliant but untested chemist named John Lunn as his apprentice. The handoff was explicit: Lunn trained under Backus for roughly a year before taking over as Master Distiller, with Backus’s signature appearing alongside Lunn’s on commemorative Barrel Select bottles. The inscriptions on the glass and multiple contemporary reports trace the arc clearly: Backus, the long-serving master who stewarded the brand through the glut, merger, shutdown, and restart; Lunn, the successor who carried the whiskey thief forward. Backus’s relationship with Lunn remained a matter of record even after the baton passed. Industry press later summarized it succinctly: Backus recruited Lunn, taught him the Dickel way, and retired the following year, leaving Lunn to serve as Master Distiller for more than a decade before moving on himself in 2015. In all, no one reveals exactly how long Dave Backus worked in Cascade Hollow, and Backus never has said. Estimates, however, are in the neighborhood of 40 years.

Inside the operation, Backus had also worn executive stripes. During the early-2000s turbulence, he was identified not only as Master Distiller but also as company President, a dual role underscoring how closely production and management were linked at Cascade Hollow. Later business listings continued to show him as executive officer for the Tullahoma facility, proof that even as the public spotlight moved to his successor in the stillhouse, Backus’s name remained connected to the place.

If one traces the tasting notes and lot codes across Dickel’s bottles from that era, it is easy to read Backus’s judgments in oak and time. He spoke plainly about production, about the temperate charcoal mellowing and the virtues of the well-guarded spring, and he treated the inventory pause just as it was; not as failure but as stewardship. When tourists returned to Cascade Hollow in 2004, the signatures on their souvenir bottles of Backus and the newly minted Lunn were a quiet reminder of continuity. The house style endured because the people who kept it had lived with it, in good years and lean ones, until it ran in their veins.

Backus’s profile in the broader whisky conversation has always been understated, perhaps because he spent most of his career inside a single hollow, tending a single tradition. But the historical record is clear on the essentials: a lifetime at Dickel; Master Distiller by 1978; calm leader through a gray shutdown period. Dave Backus is the man who restarted the stills and prepared a successor; and a family man anchored in Coffee County. That is a Tennessee whisky life, measured not in press clippings but in barrels filled, cared for, and opened at just the right moment.

Dave, now 83, and his wife, Vicki, still make their home in the Normandy area of Coffee County, Tennessee, very near where they raised their now-adult daughter, Cara.

Sources:

Herald-Tribune (Sarasota, Florida), “Sippin’ ‘whisky’ flowing again at Dickel distillery,” Karin Miller, September 28, 2003

The Whisky Room blog, “George Dickel No. 8 vs. No. 12,” October 31, 2014

The Whisky Reviewer, “John Lunn Leaves George Dickel,” Richard Thomas, March 13, 2015

Some photos courtesy of Whiskey Auction

Contributed by Tracy McLemore, Fairview, Tennessee

Ultra-rare 2005 bottle of Dickel Barrel Select signed by both John Lunn and Dave Backus.

Three of George Dickel’s currently most celebrated Tennessee Whiskies: 15-year, 17-year, and 18-year