Harry Publicker

Continental Distilling—>Rittenhouse

A Distilling Pioneer: Early Life and Immigration

Harry Publicker was born in the Ukraine on April 15, 1867, then part of the Russian Empire. At the age of six, he immigrated to the United States with his family, fleeing the persecution of Jews in their homeland. Settling in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Publicker family faced the challenges of starting anew in a foreign land. Little is known about Harry’s early years, but his humble beginnings as an immigrant shaped his drive and entrepreneurial spirit. By the time he married Rose Weinstein, he was working as a barrel maker, a trade that would inadvertently set the stage for his future in the alcohol industry.

Entry into the Distilling Industry

Publicker’s foray into the distilling world began modestly in 1913, when he started “sweating” whiskey residue from old barrels to extract and sell the absorbed alcohol as industrial alcohol. This resourceful approach demonstrated his knack for identifying opportunities in overlooked areas. Unsatisfied with this small-scale operation, Publicker took a bold step, establishing a distillery on the Philadelphia riverfront between Bigler Street and Packer Avenue. This marked the inception of Publicker Industries, Inc., a company that would grow into a titan of the distilling world.

The timing of Publicker’s entry into the industry was fortuitous. During World War I, his distillery supplied alcohol products to the U.S. government, capitalizing on the demand for industrial alcohol. Prohibition, enacted in 1920, posed a potential threat, but since it did not ban the production of industrial alcohol, Publicker’s business thrived. By the early 1920s, the distillery’s production capacity skyrocketed from 6 million to 60 million gallons, accounting for 17% of the nation’s industrial alcohol production, which was capped at 70.5 million gallons by federal regulations.

Expansion and Innovation

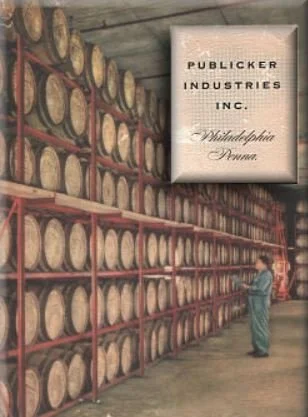

With the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, Publicker Industries seized the opportunity to enter the potable spirits market. The company formed a subsidiary, Continental Distilling Corporation, and remodeled a smaller distillery at Snyder Street and Swanson Avenue. That same year, Publicker registered the Charter Oak brand for a range of spirits, including bourbon, rye, rum, gin, brandy, and cordials. The company’s 40-acre Philadelphia plant became one of the world’s largest distilleries by the mid-1950s, producing not only whiskey but also industrial products like solvents, cleansers, antifreeze, and livestock feed from nutrient-rich waste materials. The complex included 20 buildings, 35 storage tanks, over 400 railroad cars, and a fleet of ocean-going tankers operated by its subsidiary, PACO.

Publicker’s success was driven by his ability to leverage scale and modern technology. His distillery was serviced by major railroads, enhancing distribution capabilities, and the company’s innovations in industrial alcohol production set it apart from competitors. During World War II, government contracts further propelled Publicker Industries to new heights, solidifying its status as a major player in both industrial and beverage alcohol markets.

Personal Life and Philanthropy

Harry Publicker’s personal life reflected his success. He lived on a 175-acre estate in Berwyn, Pennsylvania, and was a noted philanthropist, contributing to various causes in Philadelphia. He and his wife, Rose, had three children: Helen, Robert Bertram Mangold, and another son. Helen, his only daughter, married Simon “Si” Neuman, who would later play a significant role in the company’s trajectory. Harry’s wealth was substantial, with his will reportedly leaving $125 million, though family members contested it after he suffered a stroke in the 1940s.

Legacy and Decline

Harry Publicker’s death on March 16, 1951, at 74, marked a turning point for Publicker Industries. After a prolonged illness, he passed away in his apartment at the Warwick Hotel in Philadelphia. His son-in-law, Si Neuman, took over as chairman, expanding the company’s reach with new plants in Texas and Scotland, including the Inver House brand, named after Neuman’s 30-room Radnor mansion. However, Neuman’s ambitious expansions and poor business decisions, coupled with external factors like the Cuban Revolution disrupting molasses supplies, led to financial difficulties. By 1976, when Neuman died, Publicker Industries was $39 million in debt.

The company’s decline accelerated after Neuman’s death. Overproduction of whiskey and scotch, failure to modernize, and lack of a clear successor contributed to its downfall. By 1982, the Philadelphia plant was idled, and in 1986, the company was sold for a fraction of its former value. Environmental mismanagement led to the site being declared a Superfund site by the EPA, requiring over $20 million in cleanup costs. The once-thriving distillery was reduced to a storage yard for imported cars, and the Publicker family’s fortune dissipated amid legal battles and mismanagement.

Impact and Remembrance

Harry Publicker’s legacy is a quintessential American rags-to-riches story, emblematic of immigrant ambition and ingenuity. His distillery not only shaped Philadelphia’s industrial landscape but also left a lasting mark on the global alcohol industry. Brands like Old Hickory Bourbon and Rittenhouse Rye, produced by Publicker Industries, remain in circulation today, though under different ownership.

The Inver House brand in Scotland continues to thrive, a testament to Publicker’s vision of global expansion. However, the environmental and financial scandals that followed his death tarnished the company’s reputation. The Publicker Distillery site, once a symbol of industrial prowess, became a cautionary tale of mismanagement. Yet, for those who remember crossing the Walt Whitman Bridge and smelling the whiskey in the air, Harry Publicker’s contributions to Philadelphia’s industrial history remain unforgettable.

Contributed by: Mike Petrarca, Charlestown, West Virginia